Fellini

June 13, 2020 - June 19, 2020

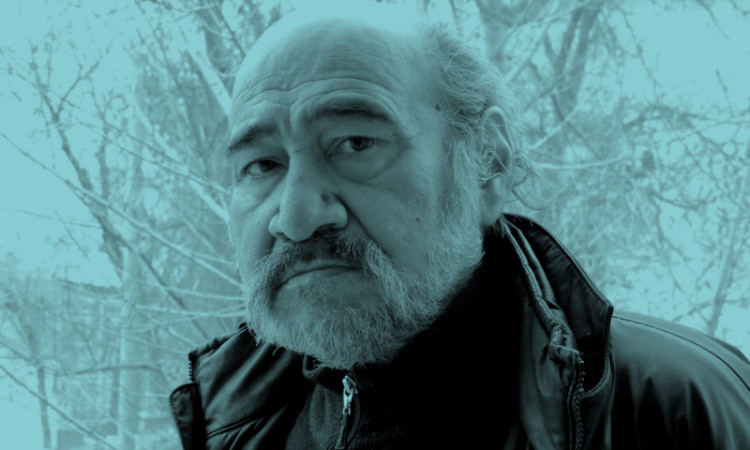

In the city of Karakalpakstan, the old cinema is living out its last days. Once upon a time, here was the shore of the Aral Sea, full of life, and the local cinema flourished. But the Aral Sea has dried up and the country has changed. Fellini, the cinema’s current owner, is the film’s main character.

Fellini: a prophetic dream-movie

The name of the film by Nazim Abbasov produced in 1999 – “Fellini” – might sound strange out of context. It refers to the great bearer of the name, and the legendary director's flair involuntarily pops up in the space between the audience and the film, creating images and associations that invite the viewer into a universe that borders cinema and reality. It is a universe full of people and characters, stories and fantasies.

Essay

Valerie Kim, CCA LAB participant

In the middle of the desert, where the earth is drying up with thirst, where water charges oxygen with its absence, the environment itself makes a pronounced theatricality, an exalted unnaturalness of what is happening as opposed to the oppression of natural conditions. There is a sense of the utopia in the plot, and because of this, its perception is especially unusual: strangers on the screen seem to be close to you, and their actions suddenly lend themselves to consistent logic. With general fuss and fatigue, a dial tuned to low frequencies can be felt. Understanding the film is often an internal stimulus, a driving force at once comprehensive and tectonic.

The audience feels no connection to the characters, and the viewer is plunged into a dynamic circulation of events in the remote area of Karakalpakstan. They follow a local Fellini in his fascinating adventures into the world of cinema, which appears on the horizon and attracts him like a mirage, which he has quietly observed in the darkness of his little abandoned movie theater. In this cinema house, his life makes sense, and an imaginary reality charms him and seems to give him the opportunity in this dark space to create a new dimension, to find a new reflection of himself. It is symbolic that only through its destruction and Fellini’s ensuing internal transformation does his whole existence change. This is developed throughout the whole film, which allows the viewer to experience an influx of consciousness and invent (or not) new volumes of illusions of ships that rescue.

In cinema, as in life, much happens and at the same time, nothing happens. While the deliberate absence of bright flashes often permits more complex emotions, the dynamics of what is happening on a flat-screen does not allow you to lean against the soft back of a chair and plunge into your own dreams. The connection between cinema and reality is latent but much stronger than it might seem. In the end, the fictional character Fellini, not Federico, shows shots from home movies, among which the pictures of the real Fellini are a super sacrament, no less. This absurd magic is the most fascinating invention of all time.